When Jojo Rabbit first premiered, as I mentioned last week, it received mixed reviews. At first glance, it’s not hard to see why—a film ostensibly portraying Hitler in a whimsical light is bound to unsettle some viewers. At first glance, it may look like the creators are treating something profoundly dark with inappropriate flippancy.

In the film, Hitler is presented as an older-brother figure—playful, full of boyish antics, even offering sympathetic camaraderie. Unsurprisingly, many viewers don’t know how to process this.

For starters, we’ve been trained, collectively, to approach stories as if they’re coded messages we need to decode. Our minds rush to classify what we see, asking, “Do I agree with this or not?” Americans, in particular, are accustomed to viewing stories as though they are five-paragraph essays instead of what they truly are: works of art.

This mindset makes a movie like Jojo Rabbit genuinely confusing. And I understand that.

Learning a New Language

What I struggle to comprehend, however, is when people refuse to give the film a chance to at least accomplish what it’s trying to do. The Hitler in Jojo Rabbit is not Hitler. He’s an imaginary friend created by a lonely boy.

Jojo’s father has been absent for years, and in his longing for a father figure, Jojo constructs an image of Hitler that blends the ideals he mistakenly believes he should embody with traits he would want in a father. As Jojo grows and begins to understand the truth about Hitler and the horrors of Nazism—helped by his budding friendship with a Jewish girl—this imaginary Hitler fades away, revealing the real monster beneath the facade.

At no point does the film evoke love, loyalty, or sympathy for Hitler—quite the opposite.

But let’s set that aside for a moment. Suppose someone actually created a film that showed a slightly less despicable side of Hitler. Handled carefully, that film could reflect an important truth about human nature.

Now, please don’t hear what I’m not saying. I am NOT suggesting that Hitler’s actions should be excused or softened or that we’re all mixed bags with extenuating circumstances. Far from it.

What I am saying—and this is critical—is that real villains rarely present themselves as purely villainous all the time.

And this is getting to the heart of the issue. If I had to pinpoint one of THE key differences between classical storytelling and much of today’s narratives, it would be this:

Good stories teach us how to see.

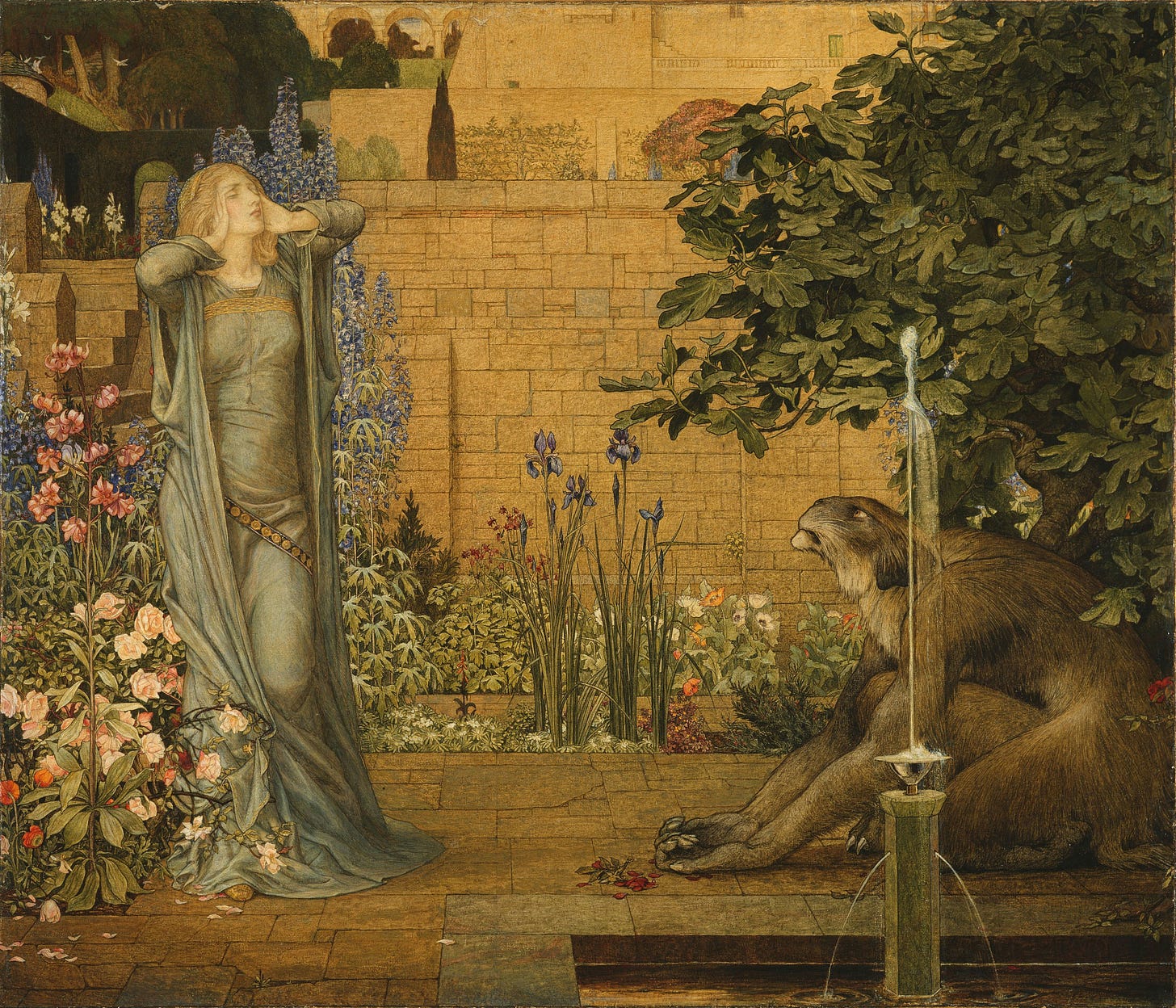

The world does not come to us the way that we moderns like our stories. Reality doesn’t come neatly labeled, tagged, and color-coded. This is why classic fairy tales often feature characters in disguise. Sometimes, the old woman is a kind soul in hiding; other times, as in Hansel and Gretel, she’s a wicked witch. Red Riding Hood is too foolish to recognize the wolf in Grandma’s bed.

To quote myself from an article about Snow White: “When the evil queen visits her in the dwarves’ house disguised as a harmless old lady, Snow White proves herself unwise. The queen came to her disguised three times, and each time, Snow White showed herself spiritually stupid.”

Good characters also often have to adopt disguises or present themselves differently, like Cinderella wearing new clothing at the ball or Odysseus returning to his hometown disguised as an old beggar. Neither one of them was recognized even by people who knew them, and that is symbolically significant.

I’ve been working my way through The Faerie Queene and recently finished the first book. It struck me that at least half of the Red Knight’s troubles—if not more—stemmed from his being so easily deceived.

“To fall (sin) is to choose an illusion, it’s not about choosing the wrong reason.”

—Northrup Frye

To give yet one more example, Jane Austen, who wrote fairy tales in the form of realism, always included at least one character who was easily duped. God himself visited earth in disguise… and I could keep going. Someone stop me!

As Aslan said, “What you see and hear depends on the sort of person you are.”

Older storytellers understood this well and wove it into their narratives. They conveyed the idea that you cannot rely solely on the evidence of your senses.

Or, again, as I wrote elsewhere: “Because evil often masquerades as light. There are wolves afoot who wear contagious smiles and work in cubicles. And there is no better way to practice discernment than in stories.”

Jojo Rabbit plays with this concept in a clever way. While the audience never doubts for a moment that the Hitler character is evil, Jojo himself must undergo a journey of discernment. He learns to see that the Jewish girl he initially assumed was a monster is actually good, while his imagined version of Hitler—a reflection of the real monster—is anything but.

A Prelude to Satire

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll recall I promised a deep dive into satire this week. And… I didn’t quite get there, did I?

In a way, though, I did. Consider this a prelude. Satire works indirectly; it hides in plain sight. That’s part of why Jojo Rabbit qualifies as satire—it approaches its subject obliquely, forcing us to think about it in new ways. By contrast, a film like Schindler’s List also addresses World War II powerfully, but it doesn’t demand the same level of active thought.

Good stories sharpen our discernment. Scripture encourages us to have our “powers of discernment trained by constant practice to distinguish good from evil” (Hebrews 5:14).

So stay tuned for next week, when I’ll delve deeper into satire. And I’m not quite done with Jojo Rabbit, either.

Another well written piece, I’m so glad to have upgraded to being a paid subscriber, reading your content has been so edifying

The modern mind has been conditioned and strip of this imaginative acumen to unravel characters in the abstract. I know it took a second reading, training and conditioning my mind to see how Lewis develops this devouring beast motifs in his Narnia characters (Digory and Eustace Scrub) gotta love those names. Believe it or not, having to read charlottes web with my daughter is where the light bulb went off for me.

You’re right, people rather have the blatant, declarative, action plot of Schindler’s list, than the development and cerebral opus of JoJo Rabbit.

I’ve been trying to introduce these ideas you’ve illustrated in your compositions in my Bible studies, because you see these all over the place, but it seems futile. Sometimes it’s like one voice crying in the wilderness. My 9 year old daughter is more receptive than my adult Bible friends, they love the Rolodex systematic discussions.