The Gate, The Key, and The Bridegroom, Part One

Where do we look for inner strength?

At a park, I recently overheard a conversation between a mom and her friend. Referring to her son, Mom said, “He is very good at self-advocating and speaking up when he thinks something is not fair.” Her friend was nodding encouragement like a bobble head.

So… there is not a child alive who does not speak up when things are not fair. I mean, do we really even need to say that? It sounded to me like she is raising a little monster—but don’t worry, I wasn’t being judgy.

When facing battles, what should we appeal to? Our own personal sense of fairness?

Playing the Field

Mariah Bertram, a character in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, seems a pillar of strength, at first. She was engaged to a wealthy man whom she did not love while keeping her options open. She toyed with the thought of dumping him for another guy. A self-advocating, societal queen… she held all the cards.

One day, she was walking with Mr. Rushworth, her fiancé, across his property, and Henry, her would-be lover. On reaching a closed, locked gate to a private garden, Mariah wanted in. It was hot, and the garden looked shady, and lovely besides.

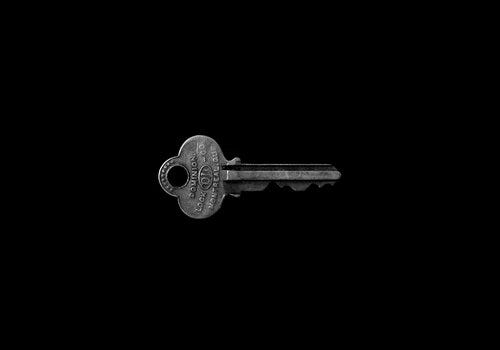

Her bridegroom had not brought the key. He had thought of bringing it but alas, keyless they remained, so Mr. Rushworth struck out, racing back to the house in search of it. Impatient, Mariah was not pleased. She said, “That iron gate, that ha-ha, gives me a feeling of restraint… I cannot get out as the starling said.”

Henry whispered, “And for the world you would not get out without the key and without Mr. Rushworth’s authority? I think it might be done if you really wished… and could allow yourself to think it might not be prohibited.”

“Prohibited! Nonsense!” She replied. “I certainly can get out and I will.”

Meanwhile, Fanny Price—Remember Her?

The shy, mousy girl?—She watched this scene unfolding from the shadows. She watched as Mariah and Henry hopped the fence, and stole into the garden like thieves. This might not seem like such a big deal, but for Austen—as usual—there is a lot more going on than first appears.

Then and now, Mariah seems like a strong woman here, right? She does not just submit to circumstances but instead fights for her rights. A manifestation of Nietzsche’s “will to power” overcoming all obstacles.

But as P. G. Wodehouse would say, “Mark the sequel.” What happened to Mariah?

Actually, let’s set her aside for the present and consider Henry, the aider and abettor of fence-hopping. An outrageous flirt, Henry was known for getting girls to fall in love with him, and then dropping them—a pre-Victorian player. This case was no different. As soon as Mariah made it clear that she loved him—that she would eagerly dump her fiancé for his sake—Henry grew bored and ghosted her.

Piqued, hurt, and smarting, Mariah married her unloved fiancé in a fit of pride and “showed” Henry. Fanny alone observed all of these events and had the wits to understand them.

A Turn of Events

Mariah, now gone and out of the way, Henry for the first time started noticing Fanny Price. He had never encountered anyone like her before. Curious, he asked around, “I do not quite know what to make of Miss Fanny,” he said to his sister. “I do not understand her… what is her character?—is she solemn—is she queer?—is she prudish? Why did she draw back and look so grave at me?”

Yet, Henry was intrigued. “Her looks say, ‘I will not like you, I am determined not to like you,’” He said, “and I say, she shall.”

Having never before met with a girl who did not respond to his flirtations, Fanny became an entirely new challenge. She become his object. At this point he wasn’t serious, he did not want to create love, he only wanted her to “give me smiles as well as blushes, be all animation when I talk to her… and feel when I go away that she shall never be happy again.”

At first he thought this would be easy. After all if he could win Mariah—a proud, headstrong beauty—how easy would it be to win a mousy wallflower? Furthermore, Fanny tried very hard to please those she cared about and when appropriate, willingly gave way to their demands. Certainly she must have been easy to manipulate, Henry assumed.

But Though She Was Quiet, She Was Not Stupid.

She saw what Henry was. She understood him while he didn’t get her at all. For the first time, Henry encountered a real challenge. When he did not succeed right away, he grew that much more determined. Fanny was just annoyed.

Then something unexpected happened. Henry began to recognize her hidden worth, and fell in love with her in truth. He found himself on the other side of that equation. This is when Fanny’s real trials began. She was attacked on all sides—attacked by him, and by her family, to accept his proposal. Everyone else was blind to his real character, only she got it. They all thought this was a no-brainer. Every girl was on the catch for Henry! Of course, mousy little Fanny will fall.

Enduring wave upon wave of pressure, Fanny remained firm, refusing him again and again. She showed a will of iron. What was going on here? What gave her strength? How could she allow herself to be ordered around by others one moment, and the next refuse to cave?

That’s for part two of this article but I will leave you with a clue: If Fanny Price had been standing by the locked gate—as Moriah had—she would have waited for the bridegroom to bring the key.

Real inner strength is not hopping every fence or casting off every restraint. It is not an insistence on what is fair. We find it only when we live according to, as Austen put it, “A higher species of self-command.”

Fanny Price possessed self-command—not self-esteem, or self love—but self-command. That makes all the difference.